Here’s part of a video that I recorded for a Lean healthcare event in Asia. I sound congested from seasonal allergies. I’m sorry about that, but there was a deadline to hit.

Creating Psychological Safety for Continuous Improvement: A Leadership Imperative

One of the most important, yet often overlooked, foundations for successful Lean and continuous improvement efforts is psychological safety. It’s not just a buzzword; it’s the difference between a culture where people feel comfortable speaking up and one where they stay silent, even when they see problems.

In the video clip, I talked about how psychological safety underpins true engagement in improvement activities. People generally want to contribute and help make things better, but they often hesitate due to fear of blame or the belief that their ideas won’t lead to meaningful change. This is where leadership plays a pivotal role–cultivating an environment where people feel safe and motivated to surface problems, share their creativity, and participate in continuous improvement.

What Is Psychological Safety?

As defined succinctly by Tim Clark (check out my podcast with him) in The Four Stages of Psychological Safety, psychological safety is a

“culture of rewarded vulnerability.”

Vulnerability, in this context, means exposing oneself to potential harm or loss by speaking up, pointing out a problem, or suggesting an idea. For many employees, especially in hierarchical organizations like healthcare, this can be risky. What if my idea is shot down? What if I’m blamed for bringing up a problem?

Fostering higher levels of psychological safety means reducing these fears. It means ensuring that when people speak up, they aren’t embarrassed, marginalized, or punished. This applies whether they’re pointing out a mistake, suggesting a process improvement, or even challenging the status quo.

Toyota and the Holistic View of Safety

At Toyota, this concept isn’t new. They view safety holistically, including both physical and psychological aspects. They don’t just focus on protecting employees from physical harm on the shop floor; they ensure that workers feel safe contributing to the improvement of processes. Toyota has demonstrated that this approach is a key element of its long-standing success with Lean and Kaizen.

In healthcare, we often focus heavily on physical safety–patient safety, employee safety–but we need to expand this to psychological safety as well. If staff don’t feel safe to speak up about problems, then those problems persist, sometimes becoming risks to both patients and the organization itself.

Higher levels of psychological safety means we’re able to achieve higher levels of staff safety and patient safety.

Why Psychological Safety Matters in Continuous Improvement

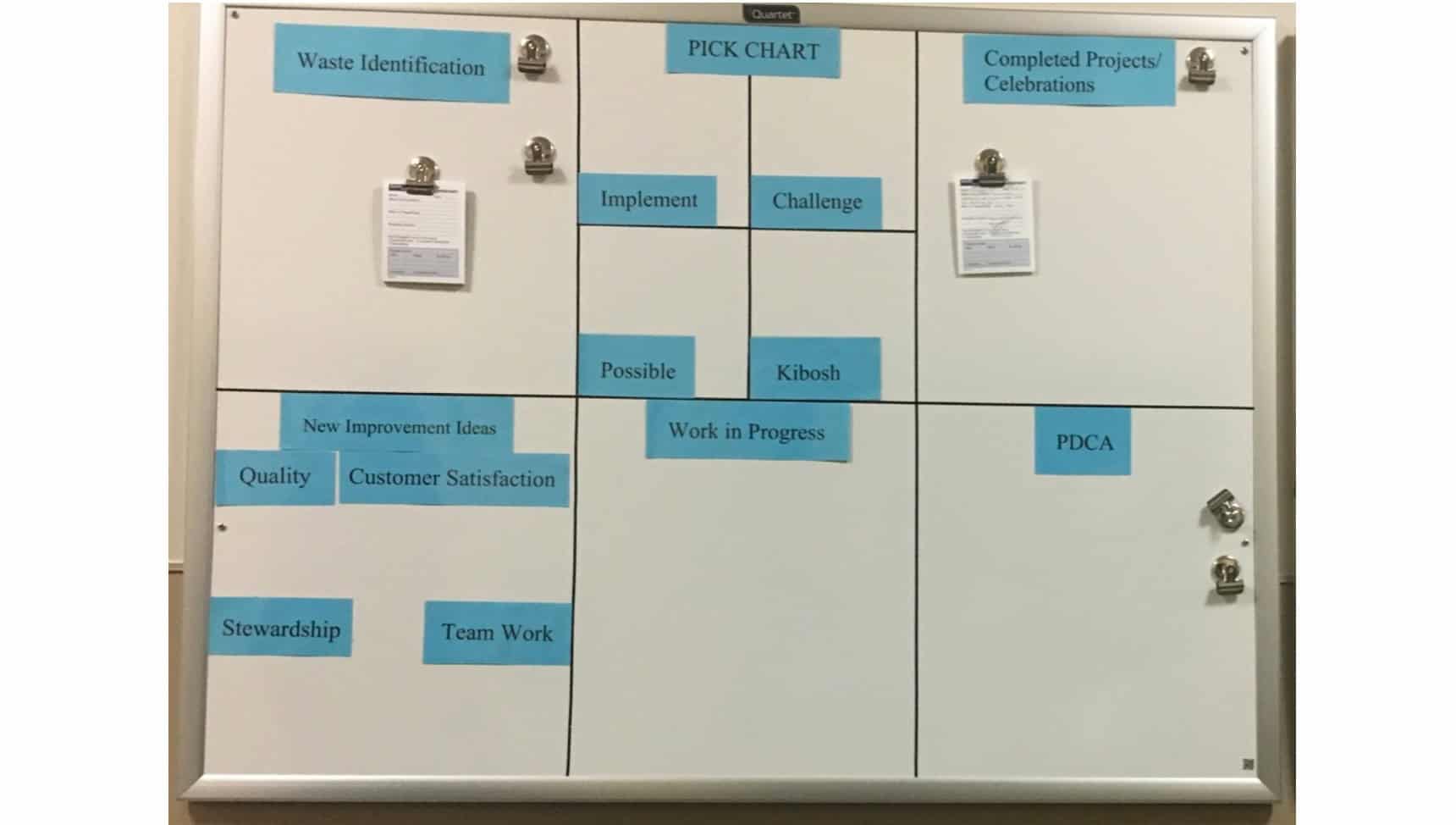

In the video, I shared an example of a hospital where a Kaizen board was installed but wasn’t being used months later. Was it that the staff had no ideas for improvement? Hardly. More likely, they didn’t feel psychologically safe to contribute. The fear of blame or the futility of feeling that “nothing will change” likely kept them from speaking up.

When people don’t feel safe, even the most well-designed Lean systems can fail. This is why I always emphasize that it’s not enough to just put tools like Kaizen boards or suggestion boxes in place. Leaders need to create the conditions where people feel comfortable using them. This requires intentional effort.

Leadership’s Role: Model Vulnerability and Reward It

As leaders, we can’t just tell people they’re safe to speak up–we have to demonstrate it. Tim Clark talks about two key leadership behaviors:

- modeling vulnerability and

- rewarding it

I think we can add a behavior in between: “encouraging vulnerability” or “encouraging candor.”

Modeling vulnerability means admitting when we’re wrong, acknowledging our own mistakes, and being open to learning in public ways. It means saying, “I don’t know.”

For example, instead of pushing an idea and assuming it’s correct, leaders can say, “I might be wrong, so let’s test this idea and see.” This approach signals that it’s okay to be wrong as long as we’re learning and improving from it.

However, modeling vulnerability is just the first step. Leaders also need to reward vulnerability when others show it. If someone points out a problem, they should be thanked–not blamed or punished. If someone suggests an idea, even if it’s not implemented, they should feel that their contribution was valued. This creates positive cycles of behavior that build higher levels of psychological safety over time.

The Consequences of a Lack of Psychological Safety

Without psychological safety, even highly motivated employees may stay quiet to protect themselves. And that’s understandable. They might know exactly what’s wrong or have an idea for how to improve things, but they’ll choose self-preservation over improvement. This leads to stagnation, where problems remain hidden and opportunities for improvement are missed.

As I discussed in Healthcare Kaizen and The Executive Guide to Healthcare Kaizen, the most powerful improvements often come from the frontline workers who are closest to the problems. But for them to feel empowered to make those changes, they need to feel safe. Leaders must remove the fear of reprisal and the futility of thinking their efforts won’t make a difference.

Fear and Futility: The Two Main Barriers to Speaking Up

Two main reasons people don’t speak up are fear and futility. Fear, as I’ve discussed, comes from the worry that they’ll be blamed, embarrassed, or otherwise punished for speaking out. Futility comes from the belief that speaking up won’t lead to meaningful action. Even if someone isn’t afraid of being blamed, they might think, “What’s the point? Nothing ever changes here.” I

‘ve heard people say, “It’s not dangerous to speak up, it’s just not worth the effort.”

Leaders can overcome this by not only fostering psychological safety but also by taking quick, visible action when people do speak up. This demonstrates that their input matters and that improvements are actually happening.

Conclusion: Psychological Safety and Organizational Success

At its core, psychological safety isn’t just about making people feel good–it’s about driving improvement and organizational success. As I’ve emphasized before, higher levels of psychological safety lead to more learning from mistakes, more creativity, and more improvement. This, in turn, leads to better results in the areas we care about most: safety, quality, delivery, cost, and morale (SQDCM).

So, how can we engage people in continuous improvement? It starts by creating an environment where they feel safe to do so. This is a leadership responsibility, and it’s one that we can’t afford to ignore if we want to sustain long-term success in Lean and Kaizen efforts.

Let’s build cultures where speaking up is encouraged, where vulnerability is rewarded, and where improvement is truly continuous.

Discussion Questions:

- What are the signs that psychological safety is either present or lacking in your organization?

- How can leaders at all levels model vulnerability and reward it?

- What steps can your organization take to create an environment where people feel safe to surface problems and suggest improvements?

Automated Video Transcript:

Mark Graban:

How do we engage people in this process? I would believe people want to participate in improvement, whether we’re using the word lean or not. I believe people want to be engaged, they want to be involved, they want to be able to use their creativity. And the foundation for this really comes down to a concept and the practices that build psychological safety. A lot of it comes down to leadership, as Toyota describes.

Mark Graban:

And I think this applies well in healthcare, the manager’s role is to develop people to surface problems and solve problems. And I think this bottom bullet point is key. Create an environment where this happens. Or we could extend that to, say, create an environment where people feel safe participating, where they feel safe to surface problems, and where they feel safe to try to improve. We can look at the literature about Toyota, including the book Toyota culture, that very directly and specifically talks about the importance of psychological safety.

Mark Graban:

It says here that Toyota uses a holistic way of looking at the safety of all stakeholders, which includes employees. It involves providing for the physical and psychological safety of each member of the team. It’s an intentional value that drives subsequent action. So we can’t just demand that people feel psychologically safe. We need to take action.

Mark Graban:

As Tim Clark, the author of the book the four stages of psychological safety, defines, psychological safety can be defined succinctly as a culture of rewarded vulnerability. Vulnerability means when we take an action, when we speak up, when we do something, that there’s the exposure to the risk of harm or loss. That risk of harm or loss could include punishment. So instead of telling people that they should be brave or that they have a professional obligation to speak up, a culture of improvement reduces the perceived risk, it reduces the fear factor so that people feel safe and they can choose to participate. Clark’s longer definition says that psychological safety is a social condition in an organization, we would say, in which you feel, and again, this is an individual perception or feeling, and this will vary within a team, across different people.

Mark Graban:

The level of perceived psychological safety will vary across a broad and diverse organization, across different teams. But when you feel psychological safety, you feel included, you feel safe to learn, you feel safe to contribute, and you feel safe to challenge the status quo, all without the fear of being embarrassed, marginalized or punished in some way. So an organization’s attempt to engage people in improvement in Kaizen and continuous improvement, without that foundation of psychological safety, we may see an improvement board that sadly looks like this, a board that’s been copied from a different healthcare organization that had active participation and continuous improvement. But in this other organization we see months later, after this was installed on the wall. The board is not being used.

Mark Graban:

I would never expect that the employees working here don’t know about the problems and that they don’t have ideas. It’s more likely a lack of psychological safety that prevents them from speaking up. If they feel like they are going to be blamed or attacked or punished in some way, they will choose to protect themselves. Even when they’re highly motivated. Intrinsically, the organization may teach them that it’s either unsafe or just not worth the effort to speak up.

Mark Graban:

The two main reasons people choose not to speak up are either due to fear or futility. So even if people aren’t afraid to speak up, if they think speaking up doesn’t lead to constructive, supportive action and improvement, people might conclude, it’s not risky, it’s not dangerous, it’s just not worth the time. So again, this comes back to leadership and their role and their responsibility in trying to help create or cultivate this culture. So what can leaders do? Again, going back to Tim Clark in his excellent book, the four stages of psychological safety, it really comes down to two key high level actions on the part of leaders at all levels, really, starting with the chief executive and other senior leaders that those leaders, first off, model these vulnerable acts.

Mark Graban:

That could include things like admitting a mistake, saying things like, I could be wrong. So let’s go test my idea in practice, that all sets a good example for others to perhaps follow. Leaders can’t just tell others to do these certain things. Leaders need to lead the way. They need to lead by example.

Mark Graban:

And when they do so, if people feel a high enough level of psychological safety, they may try to follow their lead. And when they do, leaders need to then reward these same vulnerable acts. This creates, again, more positive cycles through the organization. Leaders can’t just say the right things. They can’t just encourage people to speak up.

Mark Graban:

They certainly can’t say, you should feel safe to speak up. Leaders need to demonstrate that that is actually true by modeling and rewarding vulnerable acts. So we would see a couple of key progressions. When leaders model vulnerable acts, then people working for them may choose to follow their lead. When leaders reward these vulnerable acts, that builds a higher feeling and a higher perception of psychological safety.

Mark Graban:

Higher levels of psychological safety mean people are more likely to speak up. That means more learning from mistakes. That means more improvement, and that leads to more organizational success along the lines of SQDCM, safety, quality, delivery, cost and morale.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don’t miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

![Psychological Safety is the Foundation for Continuous Improvement [Video] – Lean Blog Psychological Safety is the Foundation for Continuous Improvement [Video] – Lean Blog](https://i2.wp.com/www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-21.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,0&ssl=1)